Clive Bull 1am - 4am

4 March 2024, 16:34

Researchers from York University worked with others from Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands.

A two-armed robot to help someone get dressed could make the process more comfortable for the person receiving care and free up time for stretched staff, a researcher has said.

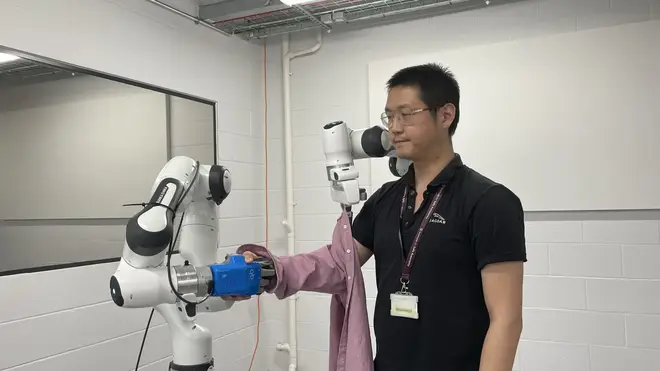

Dr Jihong Zhu, a robotics researcher at the University of York’s Institute for Safe Autonomy, has been testing a two-armed assistive dressing scheme, which he said has not been attempted in previous research.

It is suggested the approach could be more effective and comfortable than the current one-armed machines designed to help an elderly person or a person with a disability get dressed.

Dr Zhu said: “We know that practical tasks, such as getting dressed, can be done by a robot, freeing up a care worker to concentrate more on providing companionship and observing the general wellbeing of the individual in their care.

“It has been tested in the laboratory, but for this to work outside of the lab we really needed to understand how care workers did this task in real-time.”

His team used a method called learning from demonstration, meaning a human could demonstrate the movement and the robot would learn that action, as opposed to an expert being needed to programme it.

He said: “It was clear that for care workers two arms were needed to properly attend to the needs of individuals with different abilities.

“One hand holds the individual’s hand to guide them comfortably through the arm of a shirt, for example, whilst at the same time the other hand moves the garment up and around or over.

“With the current one-armed machine scheme a patient is required to do too much work in order for a robot to assist them, moving their arm up in the air or bending it in ways that they might not be able to do.”

Care England, representing social care providers across the country, said robotics can have a role in the sector but cannot replace “relationship-based care”.

Chief executive Professor Martin Green said: “With significant staff shortages in the care sector there will be increasing emphasis on finding new and innovative ways of supporting people.

“Robotics will have their place, but it must be the choice of the individual as to whether or not they want some of their care to be undertaken by robots.

“We must also acknowledge that robots can never replace relationship-based care which relies on people-to-people contact and connection.”

Caroline Abrahams, charity director at Age UK, welcomed scientific research into robotics and other technologies to support people who need help, but said that while future innovations might work alongside or even replace some of the work of human beings “we are clearly a long way from that right now”.

She said: “It’s not just that the technology needs to develop further, it’s also that it has to be manufactured in a way that keeps down the cost.

“Given that social care is, however unfairly, a low wage occupation, it’s hard to see the economics working out to allow the wholesale expansion of technology within the next few years, even if it proves possible to develop it to the degree of sophistication required.

“Some policymakers have opined that robotics are set to solve the social care workforce crisis but if so, it’s unlikely to happen any time soon.

“Today’s care workers therefore don’t need to worry about robots replacing them and, in any event, the kindness and human touch they offer is really precious and highly valued by many people who benefit from good personal care.”

Dr Zhu said the next step in their research will be to test the robot’s safety limitations such as ensuring it can be stopped or changed mid-action “and whether it will be accepted by those who need it most”.

He added: “Trust is a significant part of this process.”

Researchers said their work was in collaboration with researchers from Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands and was funded by the Honda Research Institute Europe.