Ali Miraj 12pm - 3pm

13 March 2024, 09:27

Alarm bells have been sounded over figures that show children as young as 10 are being arrested for rough sleeping.

A charity has shared figures with LBC which show a 200-year-old law is being used to ‘criminalise homelessness’ and is being used disproportionately against young people, despite a promise by the government to scrap it in 2022.

Data gathered by Centrepoint shows more than 620 people under the age of 26 have been detained by police forces across England in the past five years using the power afforded by the Vagrancy Act.

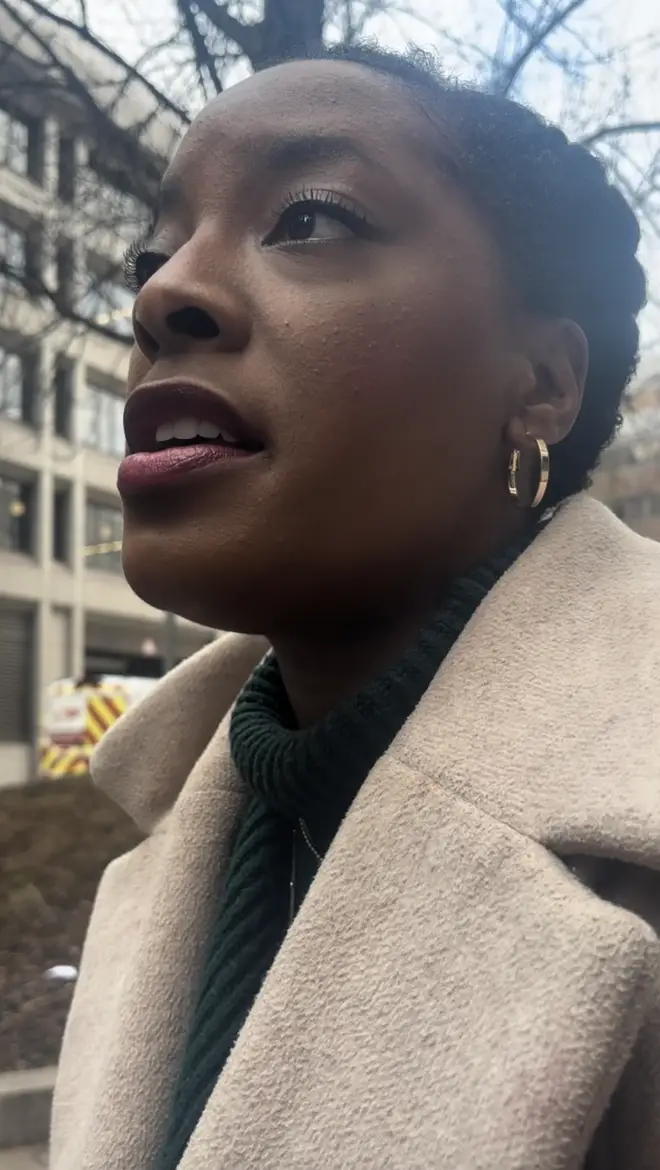

There are concerns that a new proposed law could send that figure higher. Idan* was first thrown out of her home in London when she was 15.

Read More: Children will no longer be prescribed puberty blockers after landmark NHS ruling

Meeting LBC in the city centre, bustling with tourists and shoppers, where people begging and tents and sleeping bags are a common sight, she said she feared what would happen if police came across her, trying to keep warm on trains.

“I used to sleep on the trains a lot, it felt a bit safer because you feel like anything can happen to you as a young girl.

“I’d go back and forth until it was time to go to school and then I’d get back on the train.

“Normally when I saw a police officer, I’d get off the train or pretend to sleep.

“There was one officer who basically made a joke about it, telling me to suck it up, telling me I was a big girl and my mum would be waiting for me. The advice he gave me wasn’t what I needed.

“I worried about the police all the time. I heard a lot of other peoples’ stories about how it was made out to be their fault, so every time I saw them I thought ‘I’m running’.

“I think the police need to understand that no young people choose to be homeless. The last thing you need is someone of authority scaring you more.

“I feel like I maybe wouldn’t have experienced a lot of the crazy stuff that I did if I felt like I could’ve gone to the police.”

Centrepoint, which describes itself as the UK’s leading youth homelessness charity, told LBC the fact that police can essentially arrest people for being homeless is “massively concerning”.

Their figures gathered from police forces across England show dozens of children aged as young as 10 are among those who’ve been detained.

They’ve also raised fears that in areas, the Vagrancy Act is being used against young people more often than others.

Alicia Walker, the charity’s head of policy, research and campaigns, told LBC: “We’re doing the wrong thing, we’ve got it on the wrong end and are entrenching trauma before people have even started their lives.

“How are we going to ever expect people to get out of the cycle of homelessness when we’ve created trauma after trauma for them? “The Met Police, by far, their arrests have been massively disproportionate and it’s deeply unfair.”

The figures show about 30% of the arrests made by the Metropolitan Police under the Vagrancy Act were of young people.

That’s despite a survey by London’s Combined Homelessness and Information Network (CHAIN) finding just around 10% of the city’s rough sleeping population are under 26.

A spokesperson for the Met said: "We work with partners across London to support rough sleepers and to prevent vulnerable people from becoming involved in the criminal justice system.

"Officers are encouraged to find an alternative to arrest, including the use of the Anti-Social Behaviour Early Intervention Scheme and Community Protection Notices.”

The other forces with the most disproportionate stats highlighted by Centrepoint are Thames Valley Police, West Yorkshire Police and West Mercia Police.

Walking through an area of East London with us, Alicia Walker also said she feared the language of certain politicians is playing into the problem and is leading to more young people being targeted by police.

“There’s a lot of political pressure. Homelessness is not a lifestyle choice, it’s a political choice,” she said.

“We know that politicians are choosing to talk about homelessness as though it’s a choice and therefore putting pressure on people to criminalise it.

“That’s instead of saying homelessness is something we can prevent and we want to make a change and that sort of rhetoric I think will make a massive difference in how we enforce our laws.”

Homelessness charities have warned against the government using other legislation to replace elements of the ‘draconian’ Vagrancy Act.

One concern is that the Criminal Justice Bill which is working its way through Parliament will do that but with the use of more vague language around what constitutes a ‘nuisance’ and therefore an arrest.

A spokesperson for the Home Office said: “We are determined to end rough sleeping and prevent people from ending up on the streets. Last year we published our strategy to end rough sleeping for good, backed by an unprecedented £2.4 billion.

“No one should be criminalised for having nowhere to live, which is why we are repealing the outdated Vagrancy Act, which was passed in 1824.

“Instead, we will provide a new route to engage with rough sleepers by helping them to take up offers of support and only criminalising any non-compliance.”

A government source told LBC that the proposed law under the Criminal Justice Bill would only criminalise rough sleepers where there has been some form of damage, distress or disruption to others.