Iain Dale 10am - 1pm

30 April 2020, 15:16

Can the drug remdesivir, used to treat Ebola patients, help people with coronavirus after showing "very promising" early results in trials?

Patients admitted to hospital with Covid-19 who received remdesivir recovered almost a third faster than those who were given a placebo, the initial results from a large-scale international clinical trial have shown.

Similarly, those who took the drug were also slightly less likely to die, showing a mortality rate of eight per cent, compared to 11.6 per cent for the placebo group.

The test, co-led by University College London (UCL) and the UK's Medical Research Council (MRC), has led to "cautious optimism" so far among researchers.

But the trial's director warned "we need to be careful that we don't overplay what we know" before getting too excited about the drug's efficacy.

So what is remdesivir? What happened in the drug's trial? And can it help in the fight against coronavirus?

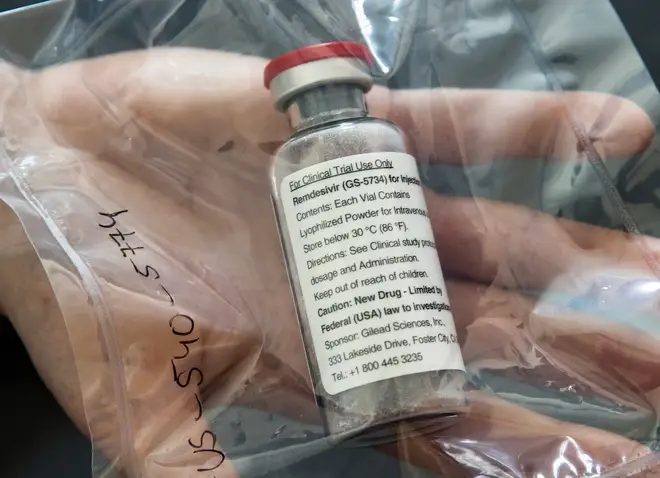

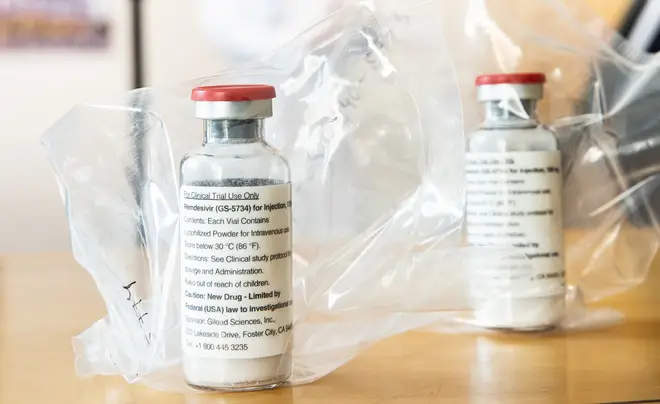

Remdesivir was originally developed by Gilead Sciences to treat patients with the deadly Ebola virus disease.

Mid-way through the last decade, the antiviral medication was swiftly pushed through clinical trials in order to help combat the 2013-2016 West African Ebola virus epidemic.

It is one of a number of drugs being trialled across the globe to see whether it would be effective in treating Covid-19.

The medication works by inserting itself into the virus' RNA chains (somewhat similar to DNA) and causes their premature termination before they can do fatal damage.

Remdesivir, being a medication, does not work in the same way as a vaccination. In simple terms, a medication cures or treats a disease, whereas a vaccination prevents and protects a person from getting a disease.

Professor in charge of coronavirus vaccine reveals how close they are

More than 1,000 patients with coronavirus, including 46 from the UK, across 70 international hospitals, took part in the Adaptive Covid-19 Treatment Trial which began at the start of April.

For 10 days, the participants were either given remdesivir or a placebo while they remained in hospital.

Their recovery - which was defined as the patients being well enough to come off oxygen, being discharged from hospital or even returning to normal activity - was monitored to see whether the medication was effective.

Results showed that people who took the drug recovered almost a third quicker than those who were given the placebo.

In addition, they showed a lower mortality rate of eight per cent, compared to 11.6 per cent for those using the placebo.

The results of the trial will now be "rigorously assessed" by regulators to establish whether it can be licenced. During that time researchers hope to obtain "more and longer-term data" from the tests and they hope to have more informative results towards the end of May.

Professor Sarah Pett, professor of infectious diseases at the UCL trials unit, paid tribute to the co-operation between teams as they worked to obtain swift results.

She said: "Delivering the results of the first stage of the ACTT study in such a short time is down to the dedication and hard work of the teams in the USA, at UCL, all of the hospitals who participated in this trial, and of course most importantly, the patients who agreed to participate."

Vaccine trials: how do they work and when could we see results?

According to the preliminary results from UCL trials, remdesivir shows "really promising" signs of helping those diagnosed with Covid-19. However, researchers acknowledged there was still "a little way to go."

While "in principle" the treatment could assist in the process of easing the UK lockdown, experts said it would depend more on dealing with transmission within the community.

Professor Mahesh Parmar, director of the MRC clinical trials unit at UCL, said: "Of course it is very exciting but we need to be careful that we don't overplay what we know to date.

"It's much better to have that discussion openly, say what we do know and what we can say, rather than in opaque press releases."

Brian Angus, Professor of Infectious Diseases at Oxford, added: "As far as the results are concerned, it's cautious optimism. There is some effect but it's not a wonder effect.

"We have to really find out when is the best time to give this drug, who benefits more - there's still a lot of data to come out of this trial."

Abdel Babiker, professor of epidemiology and medical statistics at UCL, explained: "It's the only drug where we have evidence that it helps patients and I'm sure the drug manufacturers are now in discussions with the Food and Drug Administration in the US to speed up the licensing of the drug and I'm sure they will also come to the European Medicines Agency for the same thing."

Listen & subscribe: Global Player | Apple Podcasts | Google Podcasts | Spotify