Shelagh Fogarty 1pm - 4pm

20 January 2020, 17:30

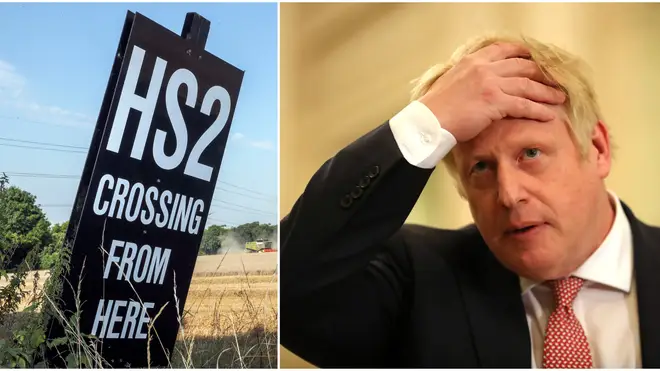

The cost of HS2 could now skyrocket to £106 billion, but what will this mean for Prime Minister Boris Johnson and the future of the project?

Today, the headlines were all about the staggering cost of HS2.

For a project that began life with a £32 billion price tag, the costs of the high-speed railway from London to Birmingham – and then Leeds and Manchester by 2040 - have spiralled.

Sir Doug Oakervee, asked last summer by Transport Secretary Grant Shapps to conduct a review into HS2, now believes it will cost £106 billion.

And while he has warned that “on balance” work should continue, Sir Doug says the service alone will not rebalance the economy and would need to be accompanied with investment in local transport.

In short, Sir Doug is giving the prime minister an out to reshape HS2, despite the £8 billion that has already been spent.

There is, of course, pressure from supporters of the high-speed railway, including the Mayor of Greater Manchester Andy Burnham and Mayor of the West Midlands, Andy Street, who wrote in The Sunday Times this weekend that high-speed rail was the “place to start” when it came to unleashing the “potential of our regions.”

For Boris Johnson, a man who told his cabinet that the Tories secured an 80-seat majority because they had been “leant” the support of traditional Labour voters, the politics are stark.

He cannot be seen to drop a project that is seen to benefit the Midlands and North, two parts of the country that might not vote Tory again on the same scale if they feel they have been let down by a government that promised them so much.

One idea that has been floated is switching HS2 around by starting work in Birmingham on the two spurs heading to Leeds and Manchester, and then completing the London leg at a later date.

The problem is that while work is ready to begin on the London to Birmingham leg, it is still far from being ready to get underway north of the Midlands.

And there is also the possibility of redirecting the money north to boost the impoverished services faced by commuters, especially those travelling across the country, rather than north to south, on a daily basis.

The problem with this idea – according to Henri Murison, director of the Northern Powerhouse Partnership – is that it is impossible to improve services in the North without new lines, as the existing railway is already operating at capacity.

Of course, the Prime Minister needs more time.

But, given the government's decision last week to step in and help the struggling airline Flybe - on the basis that it operated routes to parts of the country that were not profitable - do not be surprised if, with one eye on 2024 and keeping that promise to boost Tory constituencies that were previously safe Labour seats, Boris Johnson goes with the option that suits him best politically.