Tom Swarbrick 4pm - 6pm

24 September 2020, 14:04

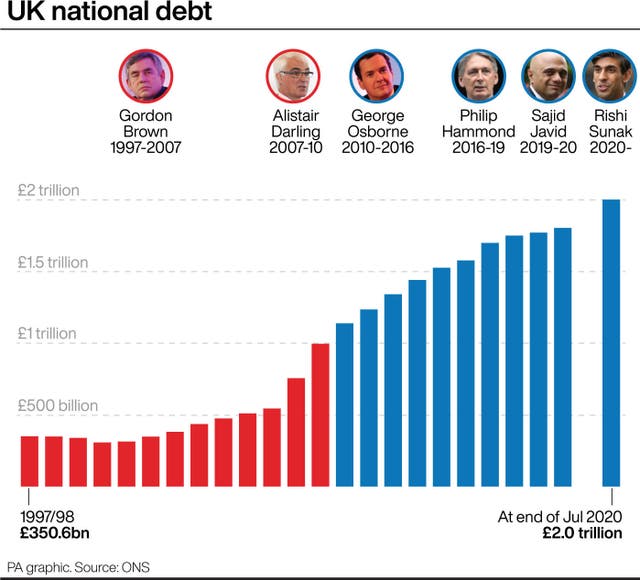

Debt levels have reached their highest point in relation to GDP since the 1960s.

How much has the government borrowed during the pandemic?

Figures released last month from the Office for National Statistics show that debt rose to more than £2 trillion in July. The statisticians are set to release updated data on Friday morning.

It is a rise of around £128 billion since March when debt was at a little under £1.9 trillion.

The data also shows that debt has reached more than 100% of gross domestic product (GDP). The Office for Budget Responsibility has forecast that net debt will rise to 106.4% of GDP by the end of the financial year.

The OBR forecasts that the Government could have to borrow up between £263 billion and £391 billion in the year ending April 2021.

The new Job Support Scheme will cost the Treasury an estimated £300 million a month for every million workers who take up the Job Support Scheme.

Why do we borrow?

As the pandemic hit, the Government announced a raft of expensive plans, for instance the furlough scheme which covered 80% of the salaries of workers who could not do their jobs.

Even in normal times, taxes paid to the Government would not have been enough to cover these schemes, and added to that, the Government is collecting less tax because the economy is doing so badly.

Governments often borrow money. What is different now – although not unprecedented – is simply the sheer scale of borrowing.

Where does the money come from?

Unlike when you ask your local bank for money to buy a house, the Government goes to lots of different places to get its hands on all the cash it needs.

It raises money by selling bonds – a promise to pay back the buyer, with interest, at the end of a fixed period.

These bonds are mainly bought by pension funds, banks, companies and people who see them as a very safe investment – safer in fact than putting cash in an account at the bank, because the bank could go bust.

Public sector net debt hits £2 trillion for the first time – read the latest commentary at https://t.co/lYraIhuyOO pic.twitter.com/KsDp6X8mXn

— Office for Budget Responsibility (@OBR_UK) August 21, 2020

How do we pay it back, and how much interest do we pay?

Because the Government borrows from so many different places, the interest it pays varies a lot.

And because the bonds are considered such a safe investment, lenders such as banks and pension funds are often willing to accept really low interests – also known as yields.

Right now, for a variety of reasons, yields are at historic lows. In fact, in May the Government borrowed money at negative yields – meaning it was being paid to borrow money.

There are no plans to start paying back the money anytime soon.

In July, Chancellor Rishi Sunak said that current debt levels are unsustainable, but he will wait until things become clearer before ensuring public finances get back on a sustainable footing.

When the Government finally decides to pay down its debt, it will likely have to use tax money to do so.

In the past, high inflation rates would naturally reduce debt levels, but today inflation rates are so low they have a very small effect on debt.

When do we have to pay it back?

We probably never will fully pay back all our debt. This is not a bad thing.

Technically each bond will be paid back after a certain amount of time, depending on the terms, but Governments often pay this by selling new bonds instead.

As Mr Sunak has said, the Government will start paying off some of the debt when things settle down, but it is very unusual for a country to pay off all its debt.

Is there a limit to how much we can borrow?

Technically, no. But it depends on if lenders are willing to lend us more. If investors think there is a chance that the UK won’t be able to pay them back, the purse strings are likely to be tightened.

Has the country ever borrowed more?

Yes and no. Government debt has never been above £2 trillion before. So by that measure debt is higher than at any point in history.

But this does not tell the whole story. A much more important measure is how much the UK is borrowing compared with how much it is producing.

Last month debt rose above gross domestic product for the first time since the early 1960s. However, the levels of debt compared with GDP is much lower than during the Second World War.