Clive Bull 1am - 4am

1 January 2021, 00:04

Britain was left nursing one of the worst recessions of all the G7 nations due to the pandemic.

It has been a year of grim records for Britain’s economy as it hurtles towards its biggest annual fall in output for more than 300 years due to the havoc wrought by Covid-19.

The UK endured its steepest recession on record, interest rates were slashed to the lowest level in history, and borrowing hit a peacetime high amid the fallout from the pandemic.

Already weighed down by no-deal Brexit fears and a year-end election, the economy entered 2020 on the back foot just as it was about to be hammered by the health crisis.

UK output rose by 1.4% in 2019, which was one of the slowest rates of growth since the financial crisis gripped the global economy in 2008 and 2009.

But last year’s woes pale in comparison with the year endured by Britain’s economy in 2020.

First described in February by former Bank of England governor Mark Carney as a potentially “sharp and large” shock to the economy, the Bank’s rhetoric quickly changed to warnings of a “very sharp” impact as the Covid crisis unfolded.

After sliding by 7.3% in March, gross domestic product (GDP) – a measure of the size of the economy – plummeted by nearly a fifth in April as Britain ground to a halt in the spring lockdown.

The UK officially entered its record-breaking recession between April and May after GDP tanked by 18.8% following a 3% fall in the first three months of the year.

This left Britain nursing one of the worst recessions of all the G7 nations, thanks to its heavy reliance on the battered services sector.

It was a baptism of fire for Mr Carney’s successor, Andrew Bailey, as he took the helm at the Bank of England in March – with his first job to slash rates to the all-time low of 0.1% as he looked to shore up the battered economy.

The Bank cut rates twice in less than two weeks in March, from 0.75% to 0.1%, while it also fired up the money-printing presses, with another £200 billion of quantitative easing (QE) to £645 billion.

It has since ramped up QE further to a mammoth £895 billion amid warnings that growth will not recover until 2022.

With little room left to manoeuvre, the Bank is exploring the possibility of taking rates below zero – in what would be yet another first for the UK.

The Bank has said it is assessing the feasibility of negative rates – which has got borrowers excited about the possibility of being paid to take out a loan.

Despite mounting expectations in financial markets for sub-zero rates, it is still far from certain if the Bank will resort to such a move.

It may have little choice if 2021 does not see a rebound in the economy as hoped.

With the year-end Brexit deadline and tighter restrictions casting a cloud over the start of 2021, the path for the economy is unlikely to be smooth.

Howard Archer, chief economic adviser to the EY Item Club, said: “The first quarter is now expected to be more challenging as a result of the new, tighter restrictions on activity.

“At best, very modest growth now looks on the cards for the first quarter of 2021, and it looks increasingly likely the economy may not grow more than 5.5% in 2021.”

The Government has spent heavily in an effort to shore up the economy and protect jobs, extending its furlough scheme until the end of April.

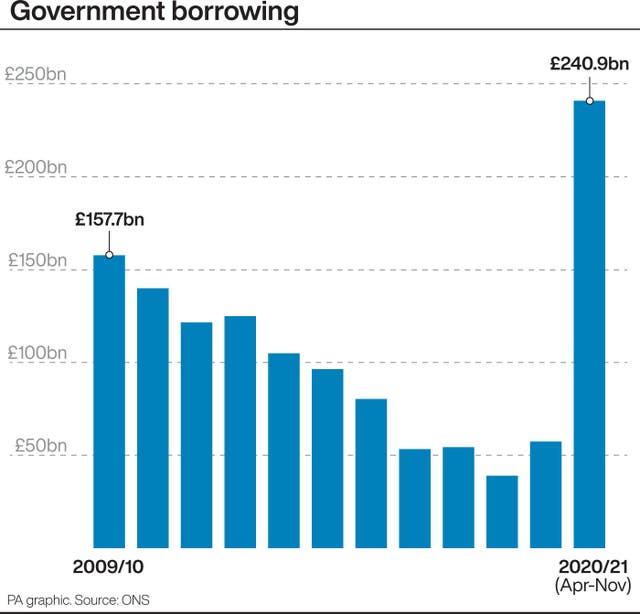

But this has not come without its cost, with Government borrowing ballooning to £240.9 billion in the first eight months of the financial year alone and predicted to reach £393.5 billion by the end of March.

While the outlook for the year ahead is far from certain, the rollout of a Covid-19 vaccine in the UK from December has given cause for hope.

Mr Archer said he expects the economy to “improve as 2021 progresses thanks to the rollout of the Covid-19 vaccines”.

Experts believe it will be at least 2022 before the economy recovers to pre-crisis levels and it is likely to emerge in a very different shape, but after a year as bad as 2020, the only way is up.